Avalanche vs The new IOTA consensus algorithm, with a touch of Spacemesh

Intro

IOTA Foundation recently announced a project called Coordicide, and an accompanying paper. The goal of the project is to remove the so-called IOTA Coordinator, a centralized service that finalizes transactions on IOTA.

The paper outlines multiple changes that are being considered in order to make it possible for the protocol to remove the coordinator and thus make IOTA completely decentralized.

One of the most interesting changes proposed is the new consensus algorithm for choosing between multiple conflicting transactions. The consensus algorithm is described in a separate paper that Dr. Serguei Popov, one of the core researchers at IOTA, published shortly before the Coordicide project was announced.

The new consensus design attracted a lot of interest because of the similarities people drew between it and Avalanche, a paper that was publicly endorsed by Emin Gun Sirer (who is also one of Avalanche’s likely co-authors) a few years ago.

DAGs of Transactions

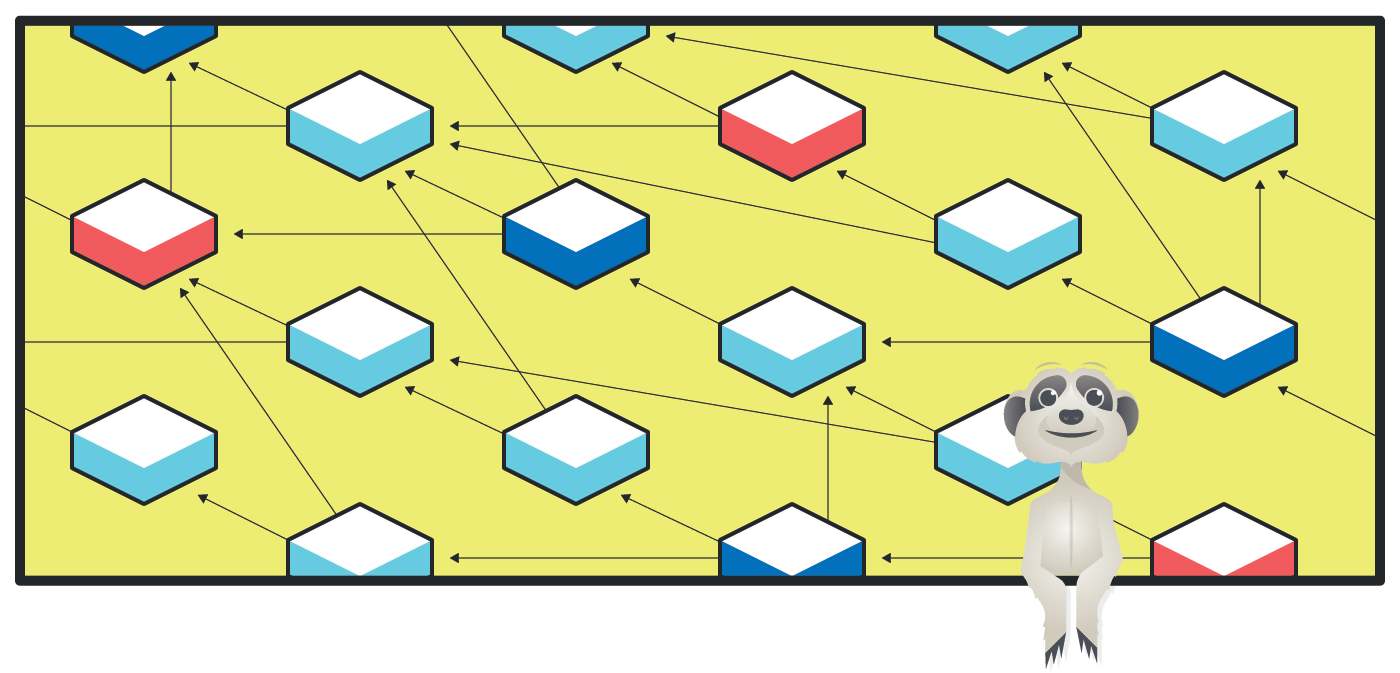

Indeed, IOTA and Avalanche are both built around a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of transactions, with edges of the DAG representing approvals.

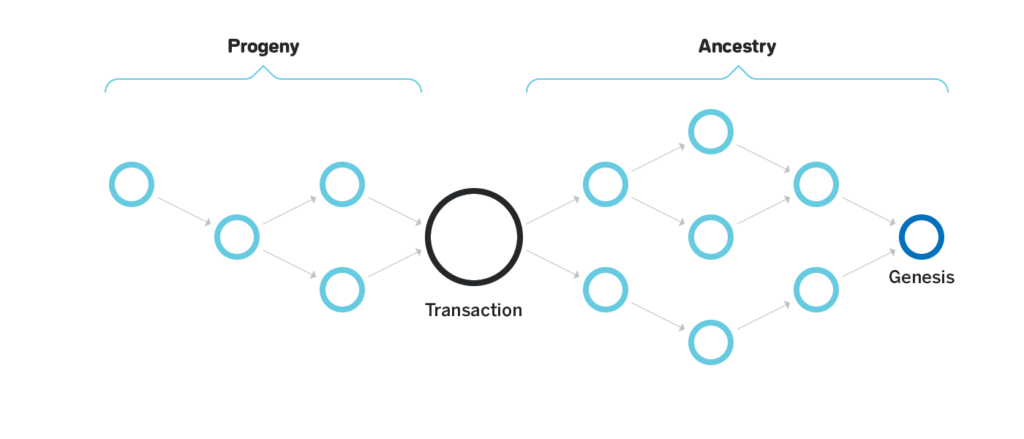

In both IOTA and Avalanche the DAG is used to reduce the amount of communication needed in order to finalize the transactions. If a certain transaction is final from the perspective of some node, then all the transactions approved by that transaction are also final (such transactions are called Ancestry in Avalanche and Past Cone in IOTA). If a particular transaction is rejected (which can only happen if the transaction spends the same UTXO as some other approved transaction) then all the transactions that approve the rejected transaction are also rejected (such transactions are called Progeny in Avalanche and Future Cone in IOTA).

Consensus

At the core of such a DAG-based protocol is the consensus algorithm that chooses one transaction amongst several conflicting transactions, i.e. transactions that spend the same UTXO. Such consensus doesn’t have to converge if multiple conflicting transactions appear at approximately the same time, and have an approximately equal number of participants initially preferring each one, since conflicting transactions can only come from malicious actors, and the protocol doesn’t need to guarantee finality for such actors. But if a particular transaction came first, and a sufficiently large percentage of participants preferred it for sufficiently long, a conflicting transaction that comes later shall never become the preferred transaction. The motivation behind this is that more transactions now exist in the Progeny / Future Cone of the transaction that arrived first, and if it gets rejected, all the new transactions from the honest nodes will get rejected too.

The consensus protocol that chooses between multiple conflicting transactions presented in the Avalanche paper is called Snowball. The consensus protocol for IOTA is presented in the aforementioned paper.

Since the consensus algorithms pursue similar goals, they also are quite similar underneath. At the core of both consensus algorithms is a node doing the following procedure iteratively until it becomes sufficiently certain that consensus has been reached:

- Choose a small sample of other nodes (on the order of 10) and query the outcome they currently prefer;

- Update the node’s current belief based on the resulting votes.

The “update the current belief” part is the core of such consensus algorithms. Since the consensus protocols need to work in the presence of adversaries that will behave in such a way as to prevent the network from reaching consensus, naive approaches (such as just preferring the outcome that was preferred by the majority of sampled nodes, or changing preference if a large percentage of sampled nodes (say 80%) believe in the opposite outcome) do not work.

Consensus properties

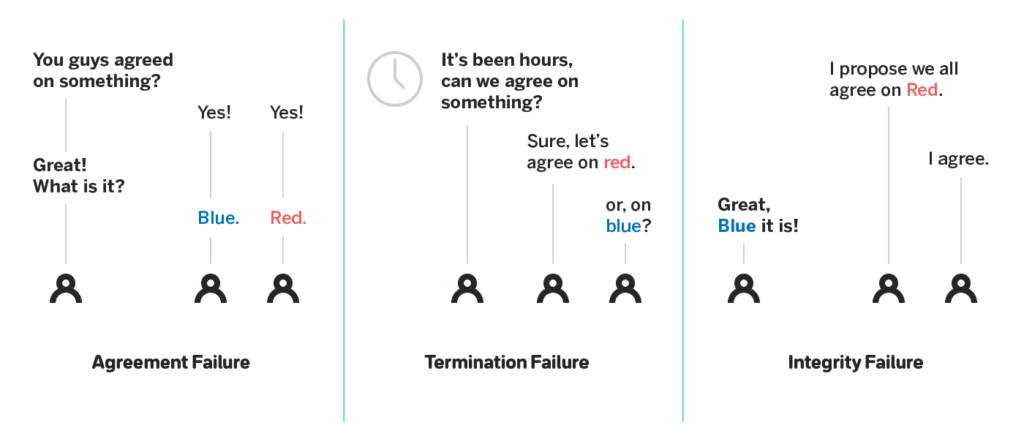

Before we proceed, let’s define what “do not work” means. There are three ways in which these consensus algorithms can break:

- Agreement failure — when two nodes both decide that some outcome was agreed upon, but those outcomes differ;

- Termination failure — when no consensus is reached after an arbitrarily long period of time;

- Integrity failure — when consensus is reached on some outcome, but that outcome was not proposed by anyone. An example of integrity failure is reaching consensus on value 0, when all the participants initially proposed the value of 1.

In the context of Snowball and the new IOTA consensus protocol, Agreement failure is absolutely not acceptable, and Integrity failure is also not acceptable, but in a slightly adjusted way. It is not only necessary that consensus is reached on the outcome that was proposed by someone, but also that if a majority of nodes were proposing some outcome, no other outcome shall be agreed upon, even if some nodes in the minority were proposing it.

The termination would also be desirable, but both protocols deemphasize it for the cases with more than one proposed outcome, arguing that more than one proposed outcome means multiple transactions spending the same UTXO, which can only come from malicious actors.

Both Snowball and the new IOTA consensus protocol provide agreement, at least as far as I can tell (though it’s important to note that the Avalanche paper has a typo that currently means Snowball doesn’t provide Agreement; with the typo fixed it is unlikely that Agreement can be violated). For both of them, it is easy to argue that if a majority of nodes initially sway towards one of the outcomes, the nodes will not switch to the other outcome no matter what malicious actors do, so Integrity (as defined above) is also present.

Termination of the new IOTA consensus and Snowball

The important difference comes when we consider Termination.

Let’s get back to the “update the current belief” part. After sampling the votes of the 10 peers a node needs to somehow adjust their current preference. In snowball each node maintains several counters to remember its confidence in each of the outcomes, and waits for several consistent consecutive samples before it changes its belief. This way adversaries cannot easily sway nodes towards one decision or the other, and cannot violate Agreement.

However, this doesn’t help much with Termination. In our simulation of Snowball we show that with the parameters provided in the paper, consensus can be kept in a metastable state for thousands of iterations if just 4% of the nodes are adversarial. With just 10% adversaries, not only does the consensus process remain in the metastable state indefinitely, but also, the nodes that believe in each outcome increase their confidence in their preferred outcome to very large numbers and continue to become more confident, bringing the consensus process into a state from which it provably cannot escape.

Thus, Snowball as-is only has Termination in the binary consensus setting with a very low percentage of adversaries. Here’s a simulation with 17% adversaries:

Read more about it here.

IOTA consensus uses a very different approach. It doesn’t maintain any counters, and instead does the following to choose between 0 and 1:

- Each node samples current beliefs of k (say k=10) other nodes;

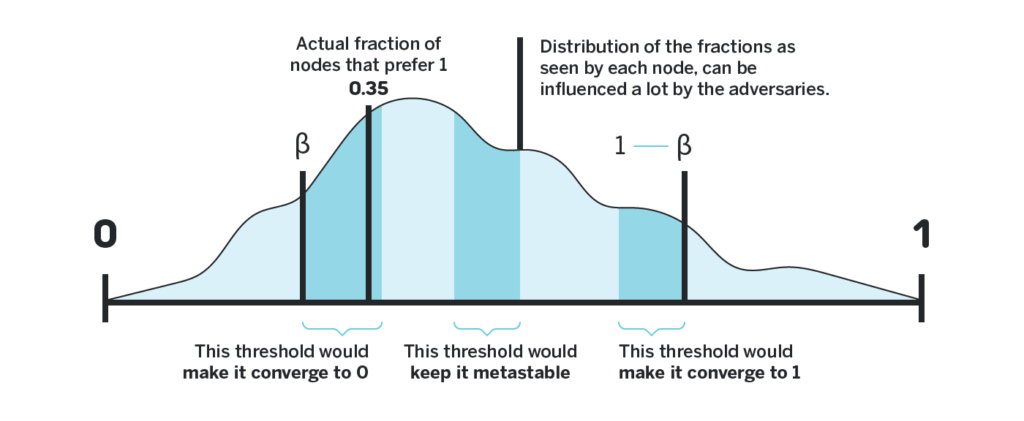

- After that, all the nodes run some distributed randomness generator to generate some threshold between some value beta and 1 – beta. I.e. if beta = 0.3, then the value will be picked between 0.3 and 0.7;

- Each node then chooses 1 if the number of nodes that prefer 1 in their sample was bigger than beta * k, otherwise it chooses 0.

The core idea here is that since the random value is chosen after the samples were performed, even an omniscient adversary (an adversary who knows the current preferences and states of all the nodes, but not the random value that will be generated in the future) doesn’t know which threshold to sway the samples towards.

To understand why this helps, imagine that the adversary can actually predict the value of the random generator, and knows it will be 0.7. If k=10, the adversary knows that in order to keep the consensus process in a metastable state, it wants approximately half of the nodes to sample less than 7 ones, and approximately half the nodes to sample more than 7 ones. If it also knows that in the current population of honest nodes 62 nodes prefer 1, it will make exactly 8 of the malicious nodes report 1 as well (so that together with the honest nodes, exactly 70 nodes report 1), and the remaining malicious nodes report 0. This way the median number of sampled ones will be 7, and thus approximately half of the nodes will end up sampling more than beta * k = 7 ones and choose one, while approximately half of the nodes will end up sampling less than 7 ones and choose zero. The adversary will then continue doing it in the future rounds, preventing the consensus process from converging.

However, consider what happens if the adversary doesn’t know the threshold. The adversary could try to report different outcomes to the different honest nodes that query them, but no matter what distribution of sampled votes they end up signalling, (with some non-trivial probability) the threshold they choose will cause a large percentage of the honest nodes to have queried samples that lie on the same side of the threshold. Thus, a large percentage of the participants will end up choosing the same outcome for the next round.

Such a consensus algorithm is significantly harder to stall. However, it relies on the existence of a distributed random number generator that generates the required randomness for the thresholds. Such randomness generation is a rather hard problem, especially given that the consensus strives for low network overhead. If Snowball had access to a distributed random number generator, the protocol’s designers could just make nodes choose the outcome of a random number generator in the event that the consensus process gets stuck in a metastable state.

For example, an idea like this is used in one of the components of Spacemesh. See professor Tal Moran explaining this approach here in a whiteboard session we recorded with him a few weeks ago.

Outro

In short, the new IOTA consensus is definitely in the same family of consensus algorithms as Snowball, but it is far from just being a Snowball copycat. As described, it is likely to have better liveness, but it relies on the existence of a distributed random number generator, which on itself is a complex problem (though the IOTA paper provides several references to existing research). If we assumed such a generator were available, it could be used in a variety of ways to escape the metastable state.

I work on a blockchain protocol called NEAR. It is a sharded protocol with a huge emphasis on usability. I wrote a lot about sharding before (see one and two), and also have a piece on usability.

Myself and my co-founder Illia often invite founders and core researchers of other protocols to a room with a whiteboard and record an hour-long video diving deep into their tech. We have episodes with Ethereum Serenity, Cosmos, Polkadot, Ontology, QuarkChain and many other protocols. All the episodes are conveniently assembled into a playlist here.

Follow myself and NEAR on Twitter to stay up to date with our progress and see new write-ups and whiteboard sessions.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog