Overview of Layer 2 approaches: Plasma, State Channels, Side Chains, Roll Ups

With the increasing adoption of blockchains, and still very limited capacity of modern protocols, many so-called Layer 2 protocols emerged, such as State Channels, Side Chains, Plasma and Roll Ups. This blog post dives relatively deeply into the technical details of each approach and their benefits and disadvantages.

The core idea behind any Layer 2 solution is that it allows several parties to securely interact in some way without issuing transaction on the main chain (which is the Layer 1), but still to some extent leveraging the security of the main chain as the arbitrator.

Different layer 2 solutions have different properties, advantages and disadvantages. The L2 solution that I personally find the most exciting is Roll Ups, which we will cover last.

Thanks to Ben Jones (Plasma Group), Tom Close (Magmo), Petr Korolev and Georgios Konstantopoulos for reviewing an early draft of this post.

State Channels

As a good introductory example of Layer 2 solutions, let’s first consider simple payment channels. Payment channels are one of the most adopted Layer 2 solutions today. Lightning Network, for example, is based on Payment Channels.

Payment channels is a specific instantiation of a more generic concept called State Channels. A good overview of the history of the state channels can be found here. State channel is a protocol between a fixed set of participants (often two) that want to transact securely between themselves off-chain, in case of payment channel specifically exchange money. The protocol for the payment channel goes as follows: two participants first both deposit some money, say $10 worth of Bitcoin, on-chain using two on-chain transactions. After the money is deposited, both participants can instantaneously send each other money without interaction with the main chain by sending to each other state updates in a form of [turn_number, amount, signature], for as long as the balances of both participants remain non-negative.

Once one of the participants wants to stop using the payment channel, they perform a so-called “exit”: submit the last state update to the main chain, and the latest balances are transferred back to the two parties that initiated the payment channel. The main chain can validate the validity of the state update by verifying signatures and final balances, thus making it impossible to try to exit from an invalid state.

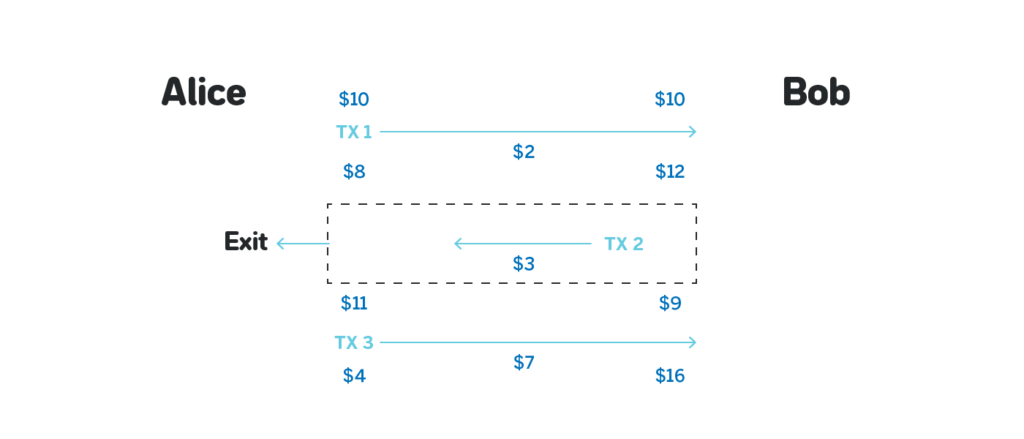

The problem with the exits is that the main chain cannot validate that the sequence of the transactions submitted is full, i.e. that no more state updates happened after those that are presented. For example, consider the following scenario:

From the state in which Alice has $11 and Bob has $9 Alice sends a state update to Bob that transfers him $7, waits for him to provide her some service for those $7, and then exits with the state update that was before she sent $7 to Bob. The main chain cannot know that an extra State Update existed, and thus sees the exit as valid.

The way to get around it is to have some time after the exit was initiated for Bob to challenge the exit, by providing a state update that is signed by Alice, and has a higher turn_number than the one that Alice submitted. In the example above Bob can submit the last state update that transfers $7 to him from Alice during the challenge period, and claim his $16 instead of just $9 in the attempted exit by Alice.

While the construction with the exit game is now secure, it presents a major inconvenience: the participants might be forced to wait for a rather long period of time to exit, usually 24 hours, and need to frequently (at least once per exit period) monitor the main chain to make sure their counterparty doesn’t try to exit using some past state. A technique called WatchTowers can be used to delegate watching the network to a 3rd party. Read more about watchtowers here and here.

To remove the necessity to wait for the exit timeout if both parties collaborate many implementations have a concept of “collaborative close”, in which participants can sign a “conclusion proof”, and the presence of such a conclusion proof allows the other party to exit without waiting for the challenge period.

The payment channel can be generalized to arbitrary state transitions, not just payments, for as long as the main chain can validate the correctness of such transitions. For example, a game of chess can be played using state channels, by players submitting their moves as transactions to each other.

Despite the inconveniences listed above, State Channels are widely used today for payments, games and other use cases, due to their immediate finality (once the counterparty confirms the receipt of a state update it is final), no fees except for those paid for the deposit and exit, and relative simplicity of the construction.

While the high level definition of the state channels is relatively simple, accounting for all the corner cases, so that no party can illegally take money from the other party, is a relatively complex task. See this whiteboard session with Tom Close from Magmo in which we dive very deeply into the intricacies of building secure state channels.

State Channel Networks

Another disadvantage of the state channels as described above is that they only exist between two participants. You can have constructions with N of N multisignatures that allow multiple parties maintain a state channel between themselves, but it would be desirable to have a layer 2 solution with properties that State Channels have, that allows parties that do not have a channel open between them directly to still transact.

Interestingly, it is possible to construct the state channels in such a way that if Alice has a state channel with Bob, and Bob has a state channel with Carol, then Alice can securely and atomically send money to Carol via Bob. With this an entire network of state channels can be built, allowing a large number of participants to transact with each other, without maintaining a connection between every pair of participants.

This is the idea behind the Lightning network. In our whiteboard session with Dan Rabinson on Interledger we dived pretty deep into Lightning Networks design, check it out here.

Side Chains

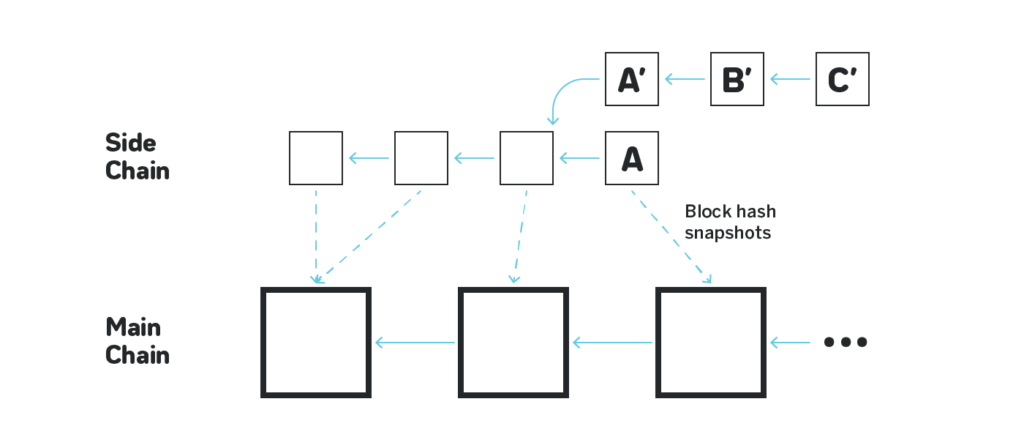

The core idea behind a simple side chain is to have a completely separate blockchain, with its own validators and operators, that has bridges to transfer assets to and from the main chain, and optionally snapshots the block headers to the main chain to prevent forks.

The snapshots can provide security against forks even when the validators of the side chain collude and try to fork out:

On the figure above the side chain produces blocks, and snapshots them to the main chain. The snapshot is just the hash of the block that is stored on the main chain. The fork choice rule on the side chain is such that the chain cannot be canonical if it doesn’t build on top of the latest snapshotted block. On the figure above even if the validators of the side chain collude and try to produce a longer chain A’<-B’<-C’ after producing block A to perform a double spend, if block A was snapshotted to the main chain, the longer chain will be ignored by the side chain participants.

If a participant wants to move assets from the main chain to the side chain, they “lock” the assets on the main chain, and provide a proof of the lock on the side chain. To unlock the assets on the main chain, they initiate an exit on the side chain, and provide a proof of the exit once it is included in the side chain block.

However, despite the fact that the side chain can leverage the security of the main chain to prevent forks, the validators can still collude and perform a different kind of attack called Invalid State Transition. The idea behind the attack is that the main chain cannot possibly validate all the blocks that the side chain produces (it would invalidate the purpose of the side chain, that is to offload the main chain from validating each transaction), and thus if more than 50% or 66% (depending on the construction) of the validators collude, they can create a completely invalid block that steals money from other participants, snapshot such a block, initiate an exit for the stolen funds and complete it.

We wrote a great overview of the invalid state transition problem in the context of sharding here. This problem maps to side chains one to one, in which case side chains would correspond to shards in the overview, and the main chain would correspond to the beacon chain.

The article linked above also covers some ways to get around invalid state transitions, but those ways are not implemented in practice today, and most side chains are built with the assumption that more than 50% (or 66% depending on construction) of validators never get corrupted.

Plasma

Plasma is a construction that enables “non-custodial” sidechains, that is, even if all sidechain (commonly called “plasma chain”) validators collude to conduct any type of adversarial behavior, the assets on the plasma chain are safe, and can be exited to the mainchain.

The simplest construction of plasma, commonly referred to as Plasma Cash, only operates with simple non-fungible tokens, and only allows transferring a particular constant amount in each transaction. It operates in the following way:

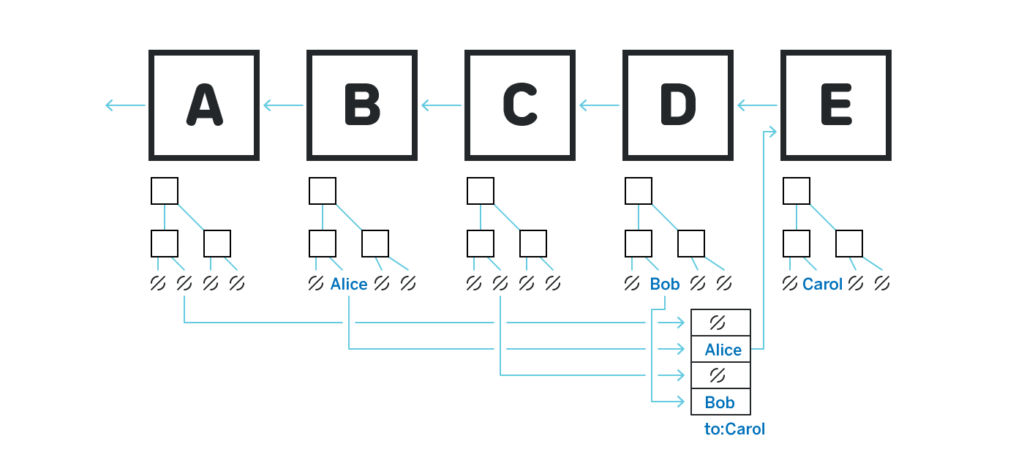

Each block contains a Sparse Merkle Tree that in its leafs contains the change to the ownership of a particular token. For example, on the above figures there are four total tokens in circulation, and in the block B tokens 1, 3 and 4 do not change hands (there’s nil in the leaf), while token 2 now belongs to Alice. If block D then contained a transaction signed by Alice that transfers the block to Bob, then the same token 2 in block D would have the transaction from Alice to Bob.

To transfer a token to someone one needs to provide the full history of the token across all the blocks that were produced on the plasma chain since the token was moved to the chain until the transaction. In the example above if Bob wants to transfer the token to Carol, then a transaction (depicted at the bottom) would include one entry per block, with a merkle proof of change of ownership or lack thereof in each block.

Plasma chain snapshots the headers of all the blocks to the main chain, and thus Carol can validate that all the merkle proofs correspond to the hashes snapshotted to the main chain, and that the change of ownership in each block is valid. Once such transaction ends up in a block of the plasma chain, the corresponding entry with Carol is written into the merkle tree, and Carol is now the owner.

Since it is assumed that the Plasma operator can be corrupted at any moment, the exits cannot be instantaneous (since the hash of the state snapshotted by the plasma operator cannot be trusted), and an exit game is required. Even for such relatively simple construction that we discussed above the exit game is pretty complex. In an episode of Whiteboard Series with Georgios Konstantopoulos from Loom Network, that goes very deep into the technical details of Plasma Cash, he presents the exit game that was used at that point by Loom Network, and we find an example where by withholding the data the operator can either steal tokens from an honest participant, or have an ability to execute a relatively painful grieving attack (see the video starting from 41:40 for the details). Later Dan Robinson proposed a simpler exit game that addressed the issue, but again an example that reorders blocks was found that broke it.

Overall, the biggest advantage of Plasma is the security of the tokens that are stored on the plasma chain. An honest participant can be certain that they will be able to withdraw their tokens no matter what of the following events occur: plasma operator creates an invalid state transition (before or after the honest participant received their tokens), plasma operator withholds the produced blocks, plasma operator completely stops producing blocks. In all these scenarios, or in general under any circumstances, the tokens cannot be lost.

The disadvantages are the necessity to provide the full history of the token when it is transferred, and the complexity of the exit games (and in general reasoning about them).

For more technical details see the episode with Loom Network mentioned above, as well as the episode with Ben Joines from Plasma Group, in which he talks about Plasma CashFlow, a more sophisticated flavor of Plasma Cash that allows transacting in arbitrary denominations.

Roll Ups

As I mentioned when discussing the side chains, one of the ways to get around the Invalid State Transition problem in side chains is to provide a cryptographic proof of correctness of each state transition. The particular instantiation of this approach presently built by Matter Labs is called Roll Ups, and was initially proposed on ethresear.ch by Barry White Hat here.

The Roll Up is effectively a side chain, in the sense that it produces blocks, and snapshots those blocks to the main chain. The operators in the Roll Up, however, are not trusted. Thus it is assumed that at any point the operators can attempt to stop producing blocks, produce an invalid block, withhold data, or attempt some other adversarial behavior.

Similar to regular side chains, the operators cannot produce fork that precedes any block snapshotted to the main chain, so once a block on the main chain that contains the snapshot is finalized, so is the block on the Roll Up chain that is snapshotted.

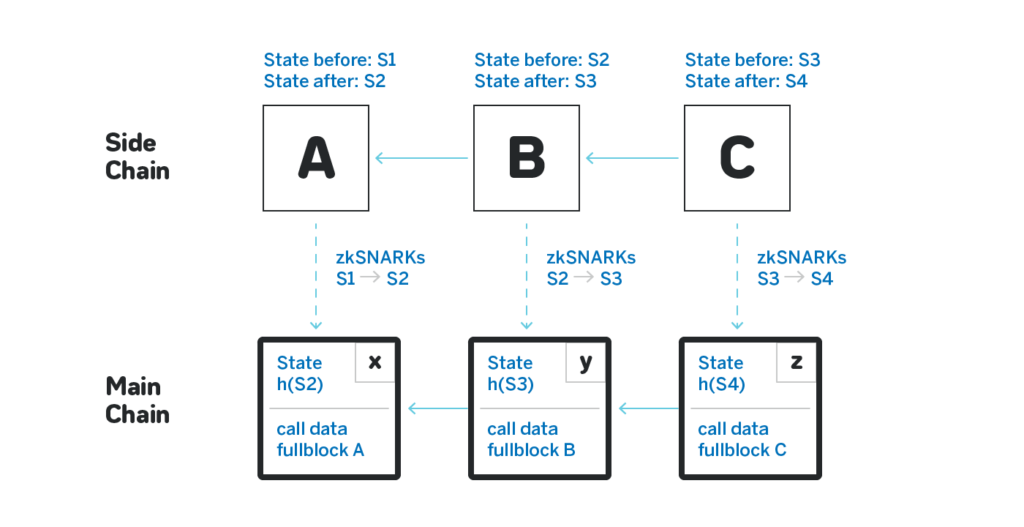

To get around the state validity issue, each time the Roll Up operator snapshots the block, they provide a snark of a list of transactions which performs a valid state transition. Consider the example below:

There are three blocks on the roll up chain: A, B and C, snapshotted correspondingly to blocks X, Y and Z on the main chain. At each point in time the main chain doesn’t need to store anything besides the last merkle root of the state of the roll up chain. When the block A is snapshotted, a transaction is sent to the main chain that contains:

- The merkle root h(S2) of the new state S2;

- Either the full state S2, or all the transactions in the block.

- A zk-SNARK that attests that there’s a valid series of transactions that move from a state hash of which is equal to h(S1) to a state hash of which is equal to h(S2), and that the applied transactions match the data provided in (2).

The transaction verifies that the zk-SNARK is correct, and stores the new merkle root h(S2) on chain. Importantly, it doesn’t store the full content of A in the state, but it naturally is kept in the call data, so can be fetched in the future.

The fact that the full block is stored in the call data is somewhat a bottleneck, but it provides a solution to the data availability issue. With the current Matter Labs implementation it takes one minute to compute the snark for a transaction (which can be done in parallel for multiple transactions), each transaction costs 1K gas on-chain, and occupies 9 bytes of call data on the main chain.

With this construction the malicious operator cannot do any harm besides going offline:

- It cannot withhold the data, since the transaction that snapshots a block must have the full block or the full state passed as an argument, and validates that the content is correct, and then such content is persisted in the mainnet calldata.

- It cannot produce a block with an invalid state transition, since it must submit a zk-SNARK that attests to the correctness of the state transition, and such a zk-SNARK cannot be obtained for an invalid block;

- It cannot create a fork since the fork choice rule always prefers the chain that contains the last snapshotted block, even if a longer chain exists.

While the amount of storage in the call data is not improved significantly with this L2 solution, the amount of the actual writable storage consumed is constant (and is very small), and the gas cost of on-chain verification is only 1k gas/tx, which is 21x lower than an on-chain transaction.

Importantly, assuming the Roll Up operators cooperate, the exit is instantaneous, and doesn’t involve an exit game. These properties combined make the Roll Up chains one of the most exciting L2 solutions today.

Outro

I work on a sharded Layer 1 protocol called Near. There’s a common misconception that sharded Layer 1 protocols compete with Layer 2 as solutions for blockchain scalability. In practice, however, it is not the case, and even when sharded protocols become live, Layer 2 solutions will still be actively used.

Designed for specific use cases, Layer 2 will remain cheaper and provide higher throughput, even when Layer 1 blockchains scale significantly better.

This write-up is part of an ongoing effort to create high quality technical content about blockchain protocols and related topics. We run a video series in which we talk to the founders and core developers of many protocols, we have episodes with Ethereum Serenity, Cosmos, Polkadot, Ontology, QuarkChain and many other protocols. All the episodes are conveniently assembled into a playlist here.

Follow me on twitter to get updated when we publish new write-ups and videos.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog